The Pis controlled the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system in each house, based on data from three off-the-shelf wireless particulate pollution sensors added to each house, two inside rooms and one under cover outside.

“With specialised software developed by the engineers, the computers were programmed to automatically turn on the air conditioning system whenever the particulate matter in the air reached a certain point and turn off the system when the particulate matter dipped below a certain measurement,” said the University.

The research was trying to work out how much HVAC energy would be required to cut pollution in the houses as well as maintain desired temperature – the HVAC systems draw air from rooms through filters, heating or cool it, then returning the it.

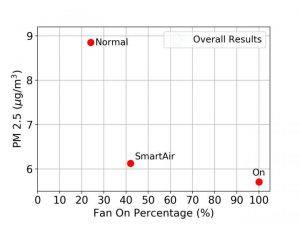

Starting at midnight each night, each home would randomly operate the sensors under one of three conditions:

- Normal – HVAC systems turned on and off normally based on temperature only

- Always on – air system operated continuously all day

- SmartAir – system turned on and off the HVAC fan based on the in-house pollution measurement, as well as the thermostat’s temperature setting.

Findings, based on five months of data, are presented today at the IEEE/ACM Conference on Connected Health: Applications, Systems and Engineering Technologies in a paper called ‘Smart home air filtering system: a randomized controlled trial for performance evaluation’.

In a nutshell: the SmartAir setting cleaned the air almost as well as if the HVAC fan was operating all day, but it used 58% less energy.

In Normal setting, air was 31% dirtier than when set to SmartAir.

According to the University, ordinary activities in the home such as cooking, vacuuming and running the clothes dryer can make air quality much worse than outside.

Photo: Utah researcher prepare the hardware

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News