Dubbed a DB-THG (drinking-bird triboelectric hydrovoltaic generator), power is extracted from the movement of the bird by the rubbing action of different materials – think rubbing a balloon on a jumper to build up charge.

Driven by the cooling effect of water evaporation and the movement of a low boiling point liquid within its glass skeleton, the bird has a two-phase action.

Starting from when its body is horizontal and its beak is in the water, it tilts back and oscillates around the vertical for a few seconds, before tipping forwards again to dip its beak into the water once more.

The generator is designed to work with these two phases.

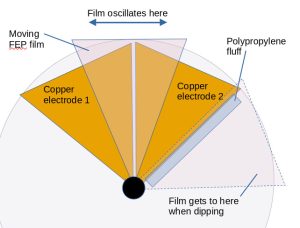

Mounted on a stationary insulated disc next to the bird are two identical adjacent copper sectors with a narrow gap between them, together occupying ~100° of the disc. The gap is aligned vertically.

Attached to the bird’s axle is a charged FEP (fluorinated ethylene propylene) sector 50° across which waves back and forth equally over the two copper sectors while the bird is oscillating.

As the polymer is charged, it alternately induces charge into the copper sectors in harmony with the oscillation.

The external circuit is connected between the copper sectors, and consequently is plied with alternating current at the bird’s frequency.

Where does the FEP sector’s charge come from?

Working charge is accumulated into the FEP sector triboelectrically, as it gently strokes past a pad of polypropylene fluff on the bird’s periodic dips into the water container – the fluff is attached to the edge of one of the copper sectors, completing the triboelectic charging ‘circuit’.

As the generator occupies less than a semicircle, a second generator was built on the other half of the stationary insulated disc, then this whole thing was duplicated on the other side of the bird, making four generators in total, which were wired in parallel.

In action, the quad-generator’s output pulses to ~200nA peak, and this is constant up to loads of ~100MΩ, but at loads below ~20MΩ the generator is effectively shorted by its load and power output is next to nothing.

However, power rises above that resistance, peaking at 30μW into 3-5GΩ.

Instead of resistive loading, the generator can also charge a capacitor, getting 1μF to 10V in 200s.

As the bird is driven by the evaporation of water, the system is dependent on ambient temperature and humidity. The researchers studied the effects of both, as well as designing a beak dipping cistern that minimised spurious evaporation.

Much to their credit, they developed a metric for water consumption, and rated their DB-THG at 6J/litre peak efficacy.

In demonstrations, it powered a calculator, a temperature sensor, or 20 small single-segment LCDs simultaneously.

“The drinking bird triboelectric hydrovoltaic generator offers a unique means to power small electronics in ambient conditions, utilising water as a readily available fuel source,” said team member Professor Hao Wu of the South China University of Technology “I still feel surprised and excited when witnessing the actual results.”

South China University of Technology worked with the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and City University of Hong Kong.

Their results are published as ‘Drinking-bird-enabled triboelectric hydrovoltaic generator‘ in the journal Device – the paper is open-access, and an enjoyable browse. Turn to the supplementary material for loading graphs and a lot more. Professor Zuankai Wang of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University is the corresponding author for the paper.

Also, the team pointed out that theirs is not the first dipping bird generator, and credits earlier magnetic designs.

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News