I have enjoyed having the chance to leaf through a copy, possibly the only paper copy, of the very first issue of Electronics Weekly. My mission: to see how electronic products and components have changed over 60 years.

And what a pleasure and an honour it has turned out to be. So many things have changed, and so many things are the same – multimeters had the same ranges as they have today, they were just a lot larger then, and they are a lot more digital now.

The lead story on the front page of Electronics Weekly Issue 1 is about Hughes setting up a low-leakage diode fab in Glenrothes – a business story, but it concludes with a note that the company was planning to introduce “an ultra-fast diode having a lifetime of less than 0.5 milli-microseconds” – not nanoseconds, because this was 7 September 1960, so the 11th Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures (CGPM) had not yet agreed the international adoption of the ‘nano’ designation, which took place one month later.

The resulting diodes did indeed surface as Hughes HD 5000, HD 5001, HD 5002 and HD 5003 in the 9 November 1960 edition of Electronics Weekly (Issue 10). They featured gold‑bonded silicon with a “guaranteed recovery time of 0.5 nanosecond” according to the paper, which was already using the new designation only a month after the conference.

The resulting diodes did indeed surface as Hughes HD 5000, HD 5001, HD 5002 and HD 5003 in the 9 November 1960 edition of Electronics Weekly (Issue 10). They featured gold‑bonded silicon with a “guaranteed recovery time of 0.5 nanosecond” according to the paper, which was already using the new designation only a month after the conference.

Oddly, that same October CGPM conference introduced Hertz as a measure of frequency, but along with many other organisations the magazine stuck with c/s (cycles/second).

Recovery time in the Hughes devices could have been faster, it was simply that 0.5ns “is given only to accommodate the measuring limits of standard sampling oscilloscopes”, according to Issue 10. (By the way, Electronics Weekly styled itself ‘EW’ as it introduced itself and its nine writers on page 2 of the first issue.)

The Hughes parts were to be made in the USA, with Hughes Glenrothes planing to run them early in 1961. The price of one was around 18 shillings – £20 each today, allowing for inflation.

These diodes were special, becoming a staple of high-end Tektronix equipment through the 1960s. Specs for the range are: <1pF 15-20Vr and 500µA to 2mA max current – the junctions must have been tiny.

I did try to find a modern equivalent, but failed as 4ns appears to be as fast as it gets for discrete silicon diodes today, even for Schottkys – one-up for 1960.

In Germany, Issue 1 reports, Siemens had just released a couple of VHF transistors for use in TV receivers, specified with 250Mc/s cut-off – some at 300Mc/s. Current gain was 2.7 at 100Mc/s, where the noise figure was 4dB. A time constant figure I have not seen before is also provided – they have an RbbCc of 18 micro-micro seconds – ‘pico’ was another designation not confirmed until that CGPM meeting.

Valvo was another German company working on VHF transistors, re‑doping its version of the PNP germanium OC171 and changing its geometry to get a gain of 2.6 and 8ps time constant at 100MHz. “These characteristics, plus the fact that it has a noise figure of 4dB at 200Mc/s, suggest that this new transistor will create considerable interest amongst TV set designers,” said Electronics Weekly, without revealing the new part number.

Germanium transistors were being made in bulk in the UK at the time, in the factory of Philips subsidiary Mullard in Mitcham, South London.

Mullard was a big player in UK electronics – its modules were used in a generation of the famous wooden Roberts Radios, for example.

The UK had around a dozen transistor fabs in the decade surrounding 1960. Take a look at Andrew Wylie’s transistor history website if you are interested.

Another page on Wylie’s site is devoted to the history of Mullard, and reveals that power transistor production was also well established in 1960, with the first European power transistor, the 24W OC16, emerging from Philips/Mullard in the mid 1950s.

Should you wish to experiment with an OC171, London-based Cricklewood Electronics still has them in stock today.

Staying with early fast components, the UK branch of RCA was advertising some rather special thermionic valves in 1960.

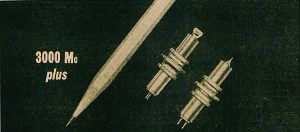

Only 41mm long and 14mm in diameter, RCA-7552 and -7554 were ‘ceramic-metal pencil tubes’ for commercial and military operation at up to 3,000Mc/s (3GHz) at altitudes up to 100,000 feet and at a heatsink temperature up to 225°C.

Only 41mm long and 14mm in diameter, RCA-7552 and -7554 were ‘ceramic-metal pencil tubes’ for commercial and military operation at up to 3,000Mc/s (3GHz) at altitudes up to 100,000 feet and at a heatsink temperature up to 225°C.

RCA‑7552 was designed for low‑noise Class-A amplifiers, and the -7554 for Class-C oscillators and power amplifiers. They were “a natural for UHF circuits in miniaturised equipment where low heater power and fast warm-up and high thermal stability are critical”, according to the advert, which added that they were “less affected by nuclear radiation than glass-metal construction”.

Missile guidance and aircraft comms were among expected uses – there is an awful lot of military electronics in Issue 1 – alongside satellite communication and data transmission, with computers and computer comms another favoured topic.

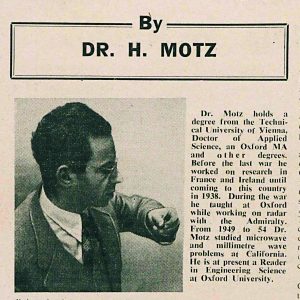

At even higher frequency, wartime radar expert Dr H Motz, at the University of Oxford in 1960, wrote a guest article about millimetre wave communication, and was about as prescient as anyone can get without a working crystal ball: “Millimetres are a very promising vehicle for telephone communication if they are piped in evacuated or gas‑filled cables. There are, for instance, a million channels of 10,000c/s bandwidth available in the band 5-6mm.

At even higher frequency, wartime radar expert Dr H Motz, at the University of Oxford in 1960, wrote a guest article about millimetre wave communication, and was about as prescient as anyone can get without a working crystal ball: “Millimetres are a very promising vehicle for telephone communication if they are piped in evacuated or gas‑filled cables. There are, for instance, a million channels of 10,000c/s bandwidth available in the band 5-6mm.

“I think we can foresee a need for so many channels. If people in Manchester get into the habit of dialling their friends in London, the demand would go up by a few hundred thousand.

“Again electronic filing might come into use. A firm with factories throughout the country might have some centralized electronic files and require to be in constant communication with their headquarters. Firms might want to feed programmes to a central computer and have the results relayed back; or distant computers might want to ‘talk’ to each other.

“Letter writing might also go out of fashion, at least for commercial purposes, if there are sufficient teleprinter channels. If the time wasted by slow communications could be calculated, the results would probably be staggering.”

You can read the rest on page 14 of Electronics Weekly Issue 1.

Motz got so many things right – especially the use of millimetre waves, now seen as the only answer for super‑high-bandwidth connections in small‑cell 5G mobile comms.

But his evacuated cables were never needed. Just five years after his article, Charles Kao and George Hockham of STC showed that fibre optics were the future for long-distance communication.

A second prescient vision of the future is buried in an article celebrating the doubling of capacity of the torroidal transformer plant of Aveley Electric, where it made mains transformers from 200W to 20kW, and also 30W and 60W audio output transformers – for which the US was the main customer.

A second prescient vision of the future is buried in an article celebrating the doubling of capacity of the torroidal transformer plant of Aveley Electric, where it made mains transformers from 200W to 20kW, and also 30W and 60W audio output transformers – for which the US was the main customer.

Something that Aveley had just introduced was the ‘Avdel’ range of transistorised dc-dc converters, and of this, said Electronics Weekly in 1960: “Prototype work now in hand indicates almost universal use of these types of unit after 1960 in all kinds of mobile, maritime, and aircraft supplies up to about 500W.”

And if you get the chance to check out Issue 1, page 12 includes a short article comparing wind, solar and nuclear power generation.

Back with that Hughes story on the front page, in a continuation on the back page, Electronics Weekly mentions that Hughes has started to make ‘core’ memory in Glenrothes.

And oh, how memory has changed in the intervening decades – probably more here than in any other aspect of electronics. Core memory stores data as non‑volatile magnetic polarisation in torroidal ferrite cores around 1mm across in a rectangular array – so density can approach 100bit/cm2 if read and write electronics are ignored.

To read and write, and to hold the array together, wires were threaded through the tiny holes in the torroids both up and down the array as well as side-to-side – some had wires threaded in both diagonal directions too.

Ridiculously fiddly to make – more knitting than lithography – it produced a memory with random access that could be read in a few microseconds.

No other array-style RAM could feature in the first issue of Electronics Weekly, as ICs of any kind were in their infancy, with a handful of transistors at most – Mohamed Atalla, Jack Kilby, Robert Noyce, Jean Hoerni and Jay Last had only made their contributions in the preceding three years.

It would be the mid-1960s before integrated circuit SRAM and DRAM were invented, and around 1970 before 1,000-bit semiconductor memories were on sale. So for a decade or more, hand‑knitted, and later machine‑knitted ferrite cores would be the only RAM in town for compact fast computer memory.

And there was great need for memory as there was huge excitement around computers in the late 1950s and early 1960s – multiple UK-built computers feature in Issue 1 – but those are [sadly]outside the scope of this article.

I had intended to make some numeric comparisons with memory then and now, but the numbers got silly. Suffice it to say: a microSD card occupies about the same area as 100 ferrite torroid bits, and the other week I bought a 32Gbyte one for £10.

On the analogue side, the iconic 741 op‑amp and 555 timer chips would have to wait for 1967 and 1970 respectively.

It was not only RAM memory that featured in Issue 1. Page 10 yields a magnetic drum from IBM that was intended to store 100kbits. A little shorter than a baked bean tin, it was specifically designed for airborne use.

It was not only RAM memory that featured in Issue 1. Page 10 yields a magnetic drum from IBM that was intended to store 100kbits. A little shorter than a baked bean tin, it was specifically designed for airborne use.

In some ways, this specialist part was a swansong, as suitcase‑sized multi‑Mbit magnetic disc memory had been built in the late 1950s, and would edge drums out over the next decade – and then keep going as a dominant memory technology even today, with 2Tbyte hard drives the size of a pack of cards available for under £100.

Just in case you have forgotten: one terabyte is eight million times bigger than a megabit – disc memory has possibly out‑paced semiconductors in the race for density.

Reading through the first issue, it is noticeable that artificial memory was only for professional, commercial or military users. No hobbyist – well, perhaps a few – would get their hands on any form of memory for another 20 years.

That said, makers were not neglected in Issue 1, as the RSGB’s (Radio Society of Great Britain’s) International Hobbies Exhibition, scheduled for November 1960 in London, is flagged on page two.

Making test equipment was, and remains, a UK speciality – although general purpose test gear is now made in the Far East, which was not the case in 1960.

As one example, a story on page 18 describes the James Scott company of Glasgow beating US manufacturers to a contract to supply four UK-grown microwave spectrum analysers to the US Navy. And there was plenty of test gear on the 7 September 1960 New Products page.

As one example, a story on page 18 describes the James Scott company of Glasgow beating US manufacturers to a contract to supply four UK-grown microwave spectrum analysers to the US Navy. And there was plenty of test gear on the 7 September 1960 New Products page.

Blackburn Electronics’ BIE 362 was there, offering a precision microvolt amplifier for instrumentation and control, with a 10 to 1,000 variable gain, 0.1% linearity, CMRR of a million to one, and total noise and drift under 5uV. Output is up to 10V at 500mA.

Forced to guess, maybe it was a chopper‑stabilised transistor amplifier?

Racal Instruments’ SA 507 was a new analogue frequency meter with ±2% linearity and options of the SA 507 optical pick-up for non-contact measurement of shaft rotation, or the MA 95B magnetic pick-up for sensing toothed wheels. All this, in an early cock-up for Electronics Weekly, was under the heading ‘Microammeter’.

FWG100 is there on the page, a sine, square, triangle and ramp waveform generator from Feedback of Sussex, which apparently operated from 0.03 to 30cycle/s – so maybe someone dropped a ‘kilo’ in the description?

And Feedback is the first name here to remain a valid company today, as Feedback Instruments is still registered in Crowborough, East Sussex in 2020, and makes the claim “with a reputation built since 1958” on its website.

Alongside Feedback on the products page, Philips was offering the GM 2877 ‘wobulator’ – a description you don’t hear often today – for checking frequency response curves of FM and TV receivers. This Dutch giant – another company that has lasted – had many UK subsidiaries in subsequent decades, including Mullard, mentioned earlier.

Alongside Feedback on the products page, Philips was offering the GM 2877 ‘wobulator’ – a description you don’t hear often today – for checking frequency response curves of FM and TV receivers. This Dutch giant – another company that has lasted – had many UK subsidiaries in subsequent decades, including Mullard, mentioned earlier.

Away from test gear on the New Products Page comes German capacitor maker Wima, the third company I’ve discovered that is still operating 60 years later. Then it was selling ‘Tropyfol’-branded capacitors with a polyterepthalic acid insulator – supplied by Waycom in the UK at the time.

These were wide temperature‑range parts, as was the other component on that page: a PTFE-insulated instrument wire range from AEI (offering “complete resistance to all known solvents except molten sodium and fluorine gas”). AEI is another company that still operates, styling itself “the world’s oldest cable company”.

It starts to look as if that first Electronics Weekly products page was not a bad place to be for company longevity, although the picture is more complex as some of those companies have been through more than one identity in the meantime.

Incidentally, the dc-dc converter company Aveley Electric, mentioned earlier, has now gone – but traces of it appear to remain in Rohde & Schwartz Services of Hampshire, according to the UK regulator, Companies House.

The advertisements in Issue 1 of Electronics Weekly mirror its product page in showing how strong UK test gear design and manufacture was in the early 1960s.

Solartron of Surrey was advertising its CD1014 dual beam oscilloscope – an ancient battered example of which was my first home oscilloscope. This had a nice dual gun CRT – so no chance of aliasing because there was no need to multiplex a single electron beam between two traces.

Cossor’s 1076 scope featured in another advert, for millimicrosecond pulses and dc to 60Mc/s, with 6-7 millimicroseconds rise time, according to the message. Cossor eventually became Ratheon Systems, which remains in Harlow Essex.

By the way, can you remember just how good analogue CRT oscilloscope displays could be? I had the chance to use one recently and, what a lovely bright, finely‑focused spot and trace. Ok, it gave no on-screen measurements or data, but it put most LCD scopes into the shade.

Contrast that with the Cintel advertisement on page 17 of Issue 1 and you also realise how digital displays have improved the life of the engineer.

Cintel was offering a 1Mc/s transistorised universal counter timer that covered six decades – ok so far – but it displayed its result on a row of six analogue electro-mechanical meters – this even though nixie tubes had been invented in the 1950s, as had dekatrons – a self-incrementing form of cold-cathode counter/display valve with a ‘carry’ output. Issue 1 was probably just too early for seven‑segment incandescent filament displays (numitrons, minitrons or pinlites) to feature.

Perhaps meters did away with the need for any high-voltage, but what a beast to read.

Southern Instruments was offering a valve-based bench-top electronic multimeter in an advert on page 19.

Ranges were 1V full-scale deflection to 2kV FSD, 1uA FSD to 2mA, and resistance stretched from 1kΩ to 100MΩ mid-scale. Accuracy was ±2% and input impedance was up to 1013Ω while voltage drop on current ranges was 5mV. Its ranges clearly lean towards measuring valve-based equipment, so maybe the writing was already on the wall for this one.

As another aside, by 1997 – admittedly 37 years later – the LT1495 op-amp data sheet had an simple circuit example that could meet the 1µA FSD spec for a quiescent current of 1.5µA. Including input protection, the 1013Ω would be tough to beat today – thermionic valves have their advantages.

An advert that seems to span the valve and transistor eras is one from Manisol of Suffolk on page 18, offering precision‑shaped glass parts – pre-forms – to be made into glass-to-metal seals, valve bases and packages for transistors and rectifier diodes, as Mansol (Preforms) Ltd is still operating today, still making precision glass parts in the same road in Haverhill, although from a factory that looks considerably younger than 60 years old.

A continuing success that advertised in that first edition was Megger – still making insulation testers today, and Texas Instruments had an advert for silicon rectifier diodes on page 12 of Issue 1 – I wonder what happened to them?

Among test gear companies that did not make it, Lancashire Dynamo had an intriguing name. Ironically based in Staffordshire, it was both advertising chart and strip recorders in Issue 1, and had a lighting control unit featured on the new products page.

Another market where the UK was doing well and continues to do well in is PCB manufacture – although the scale has changed. In September 1960, Printed Circuits Ltd was opening the “world’s largest” automated PCB factory in Borehamwood Hertfordshire, according to Electronics Weekly. This was built with the London Electric Wire Company and Smiths Ltd – a single company with a long name – which operated until 2018.

Another market where the UK was doing well and continues to do well in is PCB manufacture – although the scale has changed. In September 1960, Printed Circuits Ltd was opening the “world’s largest” automated PCB factory in Borehamwood Hertfordshire, according to Electronics Weekly. This was built with the London Electric Wire Company and Smiths Ltd – a single company with a long name – which operated until 2018.

At the chemical end of electronics, L Light & Co of Buckinghamshire had just developed a process for producing 99.999% pure phosphorus for semiconductor doping, to add to its range of 99.9995% indium and 99.9995% boron. Boron was £18 per gram then – multiply by 23 to allow for 60 years of inflation.

It was not all UK news in Issue 1 as, on the International Page, Japan was already making a name for itself, although not for test gear or components.

Toshiba had built the ‘world’s largest meteorological radar’. 600kW output at 3Mc/s gave it a range of 312 miles when spotting the eyes of typhoons through its giant parabolic dish. And Toshiba is still in the weather radar business, only three years ago taking an order for a 400km (250mile) range S-band weather radar “with an antenna in the world’s largest class”, according to the company. It is to be installed in Taiwan to supply high-resolution precipitation and wind velocity data in the area of the western Pacific known as ‘Typhoon Alley’ – once again to spot on-coming typhoons.

Toshiba had built the ‘world’s largest meteorological radar’. 600kW output at 3Mc/s gave it a range of 312 miles when spotting the eyes of typhoons through its giant parabolic dish. And Toshiba is still in the weather radar business, only three years ago taking an order for a 400km (250mile) range S-band weather radar “with an antenna in the world’s largest class”, according to the company. It is to be installed in Taiwan to supply high-resolution precipitation and wind velocity data in the area of the western Pacific known as ‘Typhoon Alley’ – once again to spot on-coming typhoons.

Sadly there is not enough room in this supplement to Issue 2777 to go on much more: do browse Issue 1 yourself when it is uploaded to the website as a digital edition.

Before I wrap up, I have to add a personal thanks to our own components editor David Manners, whose collection of early Electronics Weeklys, preserved to feed the Mannerisms blog, includes the first edition. The company’s official archive was destroyed some years ago so it is possible that the British Library now holds the only complete set.

Other brands that ‘made it’ from Issue 1 are Araldite and Formica – the latter making industrial insulating laminates 60 years ago. Plessey still exists, but only the name was carried on to today’s world-beating micro-LED fab in Devon.

Transformer-maker Parmeko almost made it, surviving until 2013 from its roots in the 1930s. The company sign was recently still to be seen on the wall of its Leicester factory.

German Siemens, of VHF transistor note mentioned earlier, lives on within Infineon today.

UK connector‑maker Harwin failed to get a mention in the first issue, but made up for that by buying an advert on the front page of Issue 2. It still operates from the same site in Portsmouth that it occupied 60 years ago, but now uses an impressive array of state-of-the-art equipment.

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News